A Mental Model About Nuance

Welcome to my sixteenth post in the Advent of Writing series.

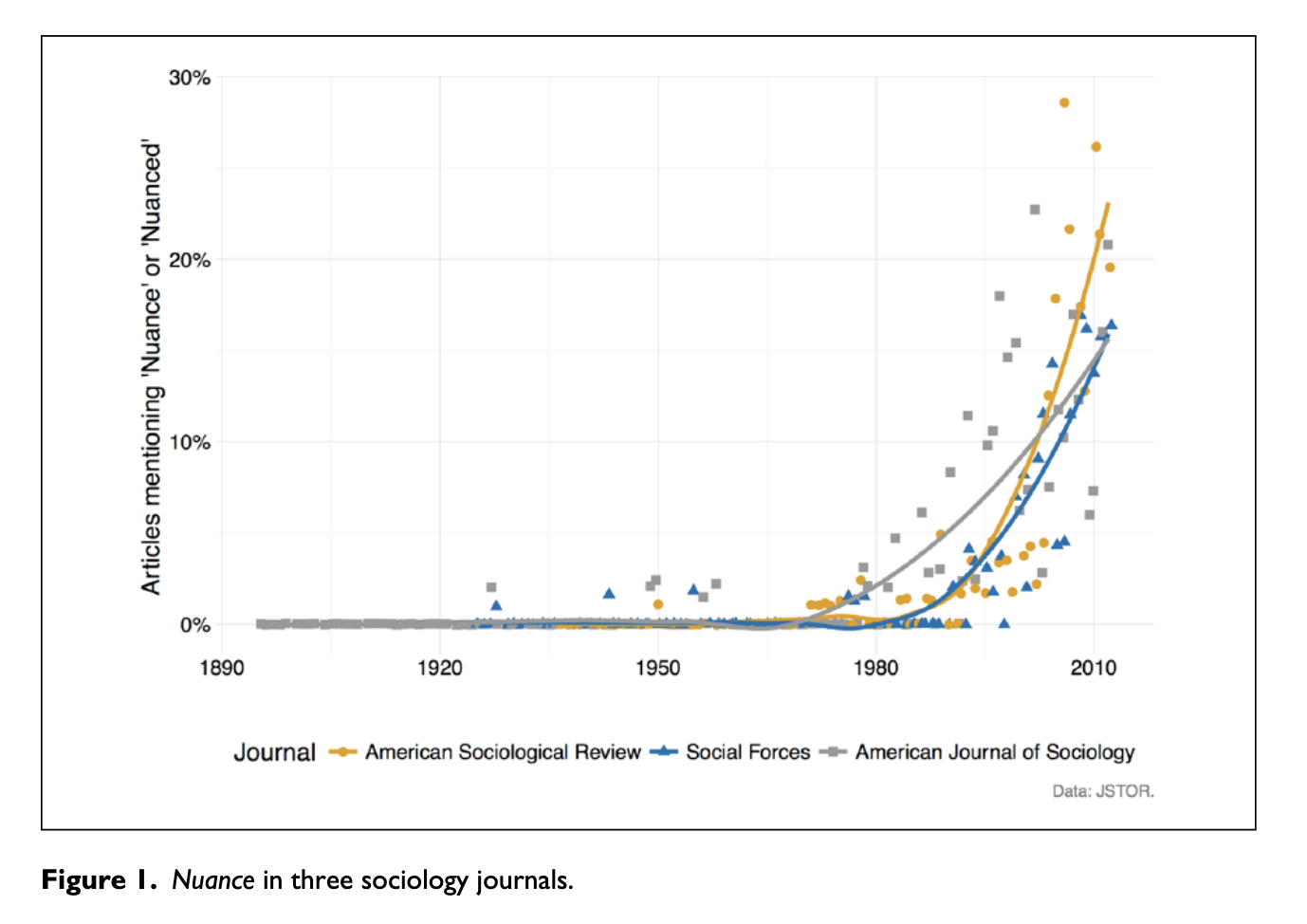

Today we will analyze this graph:

If you have not read the article, you should. The graph is from the brilliantly titled paper “fuck nuance”, where Kieran Healy identifies three distinct types of nuance traps:

- Fine-Grain: the urge to add just one more detail because it creates a sense of progress. We try to make a theory defensible from all points of view rather than broadly explanatory.

- Conceptual Framework: building a theory so large and vague that it escapes criticism by reinterpreting any claim.

- Connoisseur: culturally signaling that you are enlightened or intelligent by invoking nuance at every opportunity.

Healy discusses these traps in the context of science, but they are equally prevalent in business and many other parts of society. That is what I want to focus on here.

Nuance vs Compression

Charlie Munger was famous for his mental models of the world. In a very real sense, a mental model is a compression of reality.

Nuance is information-adding. It introduces new dimensions, exceptions, caveats, and edge cases. Compression does the opposite. It reduces while preserving meaning. It throws things away on purpose to keep only what matters. That is the interesting axis to explore.

A good mental model, meaning good compression, is a refusal to be nuanced. It commits to a dominant causal story and ignores details until they break the model. A mental model is lossy, and that is the point. You want to be approximately correct rather than precisely wrong.

Why Nuance Feels Like Progress

Nuance feels productive because it looks like movement. There are more words, more diagrams, more discussion. Something is happening.

Compression feels different. It forces you to say that this matters and that does not. Which is uncomfortable because it creates an easy way to attack your thesis. Once you compress, you are exposed.

This is why nuance is often mistaken for rigor. Nuance feels careful and sophisticated. Compression demands commitment. It asks you to bet that a small number of variables dominate the outcome.

Progress in understanding often looks like removal, not addition. A better model usually explains more with less. What changes is not the number of details included, but which details are deemed irrelevant.

Compression as an Escape from the Nuance Traps

Look again at the three nuance traps through the lens of compression. Each of them is a failure to throw information away.

The fine-grain trap is the belief that adding detail brings you closer to the truth. Each new exception feels like progress. Compression forces a more direct question: what dominates the outcome? Most systems are driven by a small number of first-order effects. Nuance lives in the margins. If you need more than a handful of variables to understand a phenomenon, you are not compressing.

Large conceptual frameworks fail by design. They are flexible enough to reinterpret any result as confirmation. Compression keeps the surface small and focuses on one clear claim. A good mental model makes statements that can fail. It tells you not only what it explains, but what would prove it wrong.

Nuance connoisseurs favor:

- jargon over plain speech

- complexity over dominance

- social validation over transfer

Compression thinkers emphasize:

- simple language

- first-order effects

- teachability

If an idea does not travel, it is probably not compressed.

Closing

Perfection in design is achieved not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to remove.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

You do not make explanations better by adding layers and layers. You make them better when you arrive at an explanation from which you cannot remove a single sentence without rendering it wrong.

That is what good compression looks like.