Simple Intro to RISC-V Assembly

In my 5th Advent of Writing blog I mentioned that I’d eventually need to write an introduction or tutorial on basic assembly. Well—this is it! I’ll go through the fundamentals with two goals in mind:

- provide a genuinely helpful guide for anyone trying to understand assembly, and

- refresh the basics for myself.

I think every programmer should be able to read at least some assembly. Very few people need to write assembly regularly, but everyone benefits from having an intuition for how things work beneath all the layers of abstraction. Modern software stacks hide so much of the machine that we easily forget what actually happens under the hood. This post is meant to be a reminder.

What is assembly?

In short: assembly is a human-readable representation of machine code. Here’s a tiny example:

mv a5, a4mv means “move,” and a5 and a4 are registers, small pieces of storage inside the CPU that you can access very quickly.

This instruction copies whatever is in a4 into a5.

Most assembly instructions follow a pattern like this: instruction, destination, source(s). In general, what you do in assembly boils down to:

- loading and storing values in registers and memory

- arithmetic and comparisons

- branches and jumps

- a handful of other simple operations

RISC-V is a great architecture to learn on because it is very minimal: around a few dozen basic integer opcodes in the RV64I base ISA. By comparison, x86 has thousands of instructions thanks to 40+ years of backward compatibility.

Example

Let’s look at what assembly this small C program produces:

#include <stdio.h>

int magic(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

int main() {

int c = magic(3,5);

printf("%d\n", c);

return 0;

}I’m compiling this using a riscv64 toolchain, but any C compiler targeting RISC-V will give similar results:

riscv64-unknown-linux-gnu-gcc -static -o demo demo.c

riscv64-unknown-linux-gnu-objdump -d demo > demo.txtWe’re going to zoom in on the magic function. Its assembly begins like this:

0000000000010406 <magic>:

10406: 1101 addi sp, sp, -32

10408: ec06 sd ra, 24(sp)

1040a: e822 sd s0, 16(sp)

1040c: 1000 addi s0, sp, 32Let’s go through this line by line.

addi sp, sp, -32

addi means “add immediate”: add a constant to a register.

So this does:

sp = sp - 32So whatever sp was before this function, it’s now that minus 32.

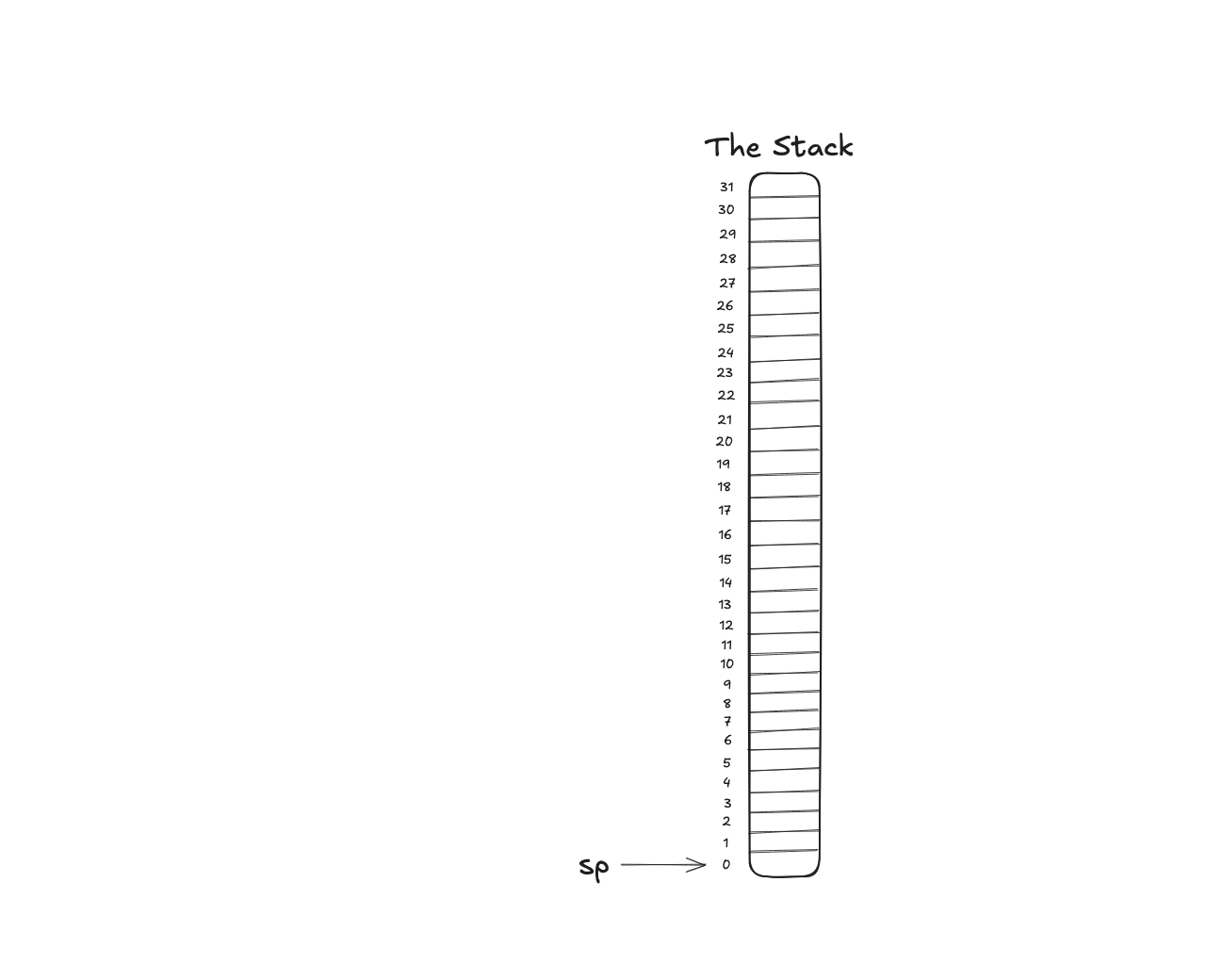

This allocates 32 bytes of stack space for the function. On RISC-V (like most architectures), the stack grows downward in memory, so subtracting from sp makes the stack larger.

The image below illustrates this: where we imagine that the previous value of sp was 32. And that means after this instruction sp is at zero. And we’ve grabbed our stack.

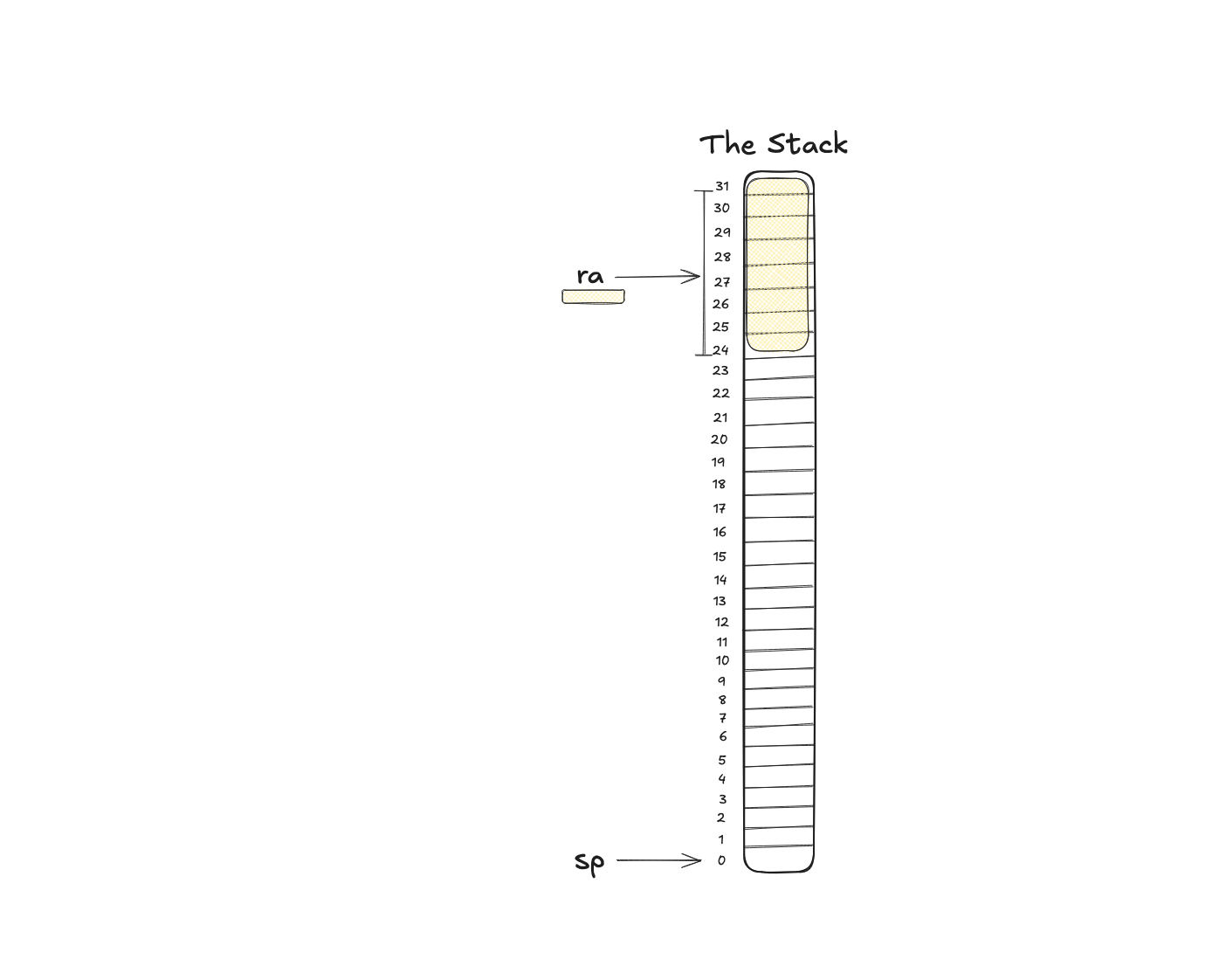

sd ra, 24(sp)

sd means “store double-word” (8 bytes on RV64).

ra is the return address register: where execution should continue once this function returns. So essentially: “where should I go once I’m done with this function?”. In our case this would be the place where main called this function.

24(sp) means sp + 24. Therefore the entire thing is:

- whatever is in

ra - store those 8 bytes in sp+24, which is 0+24=24

And that goes inside our newly allocated 32-byte stack frame, like so:

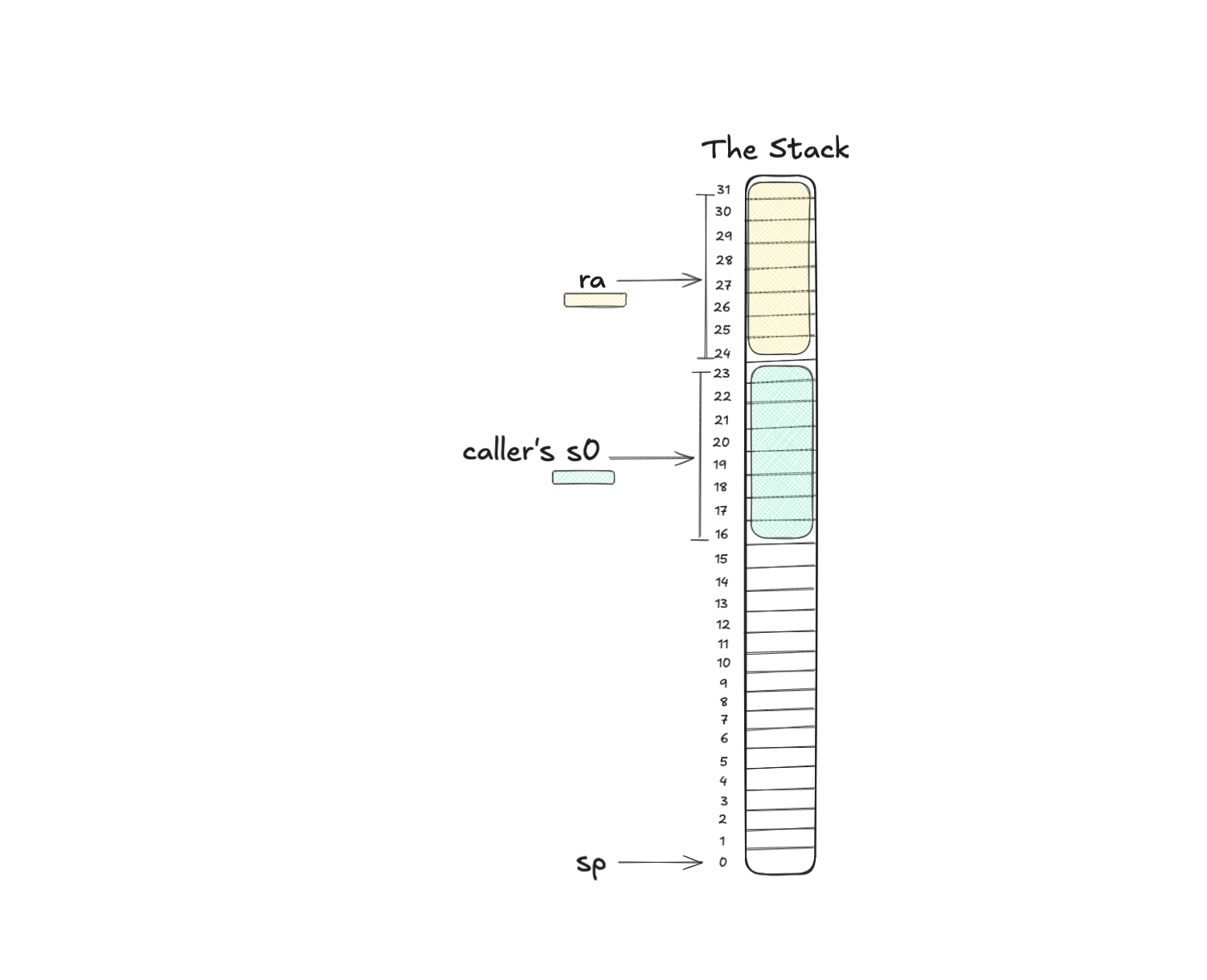

sd s0, 16(sp)

This is a similar thing in that it stores something on the stack. But this time it’s the caller’s frame pointer (s0). And we store it at sp + 16.

A frame pointer is a stable reference to the start of a function’s stack frame. So for the magic function this would be 32. But remember now we’re storing the caller’s framepointer. Why?

The reason is that we can’t just override s0 with our frame pointer, otherwise we’d lose whatever was there before. That’s why we:

- store the caller’s frame pointer on the stack (this instruction)

- override

s0with our frame pointer (next instruction) - and before exiting the function, we restore the caller’s frame pointer into

s0

Also it’s good to note that not all functions need or use a frame pointer, but compilers often generate one because it simplifies debugging and stack unwinding.

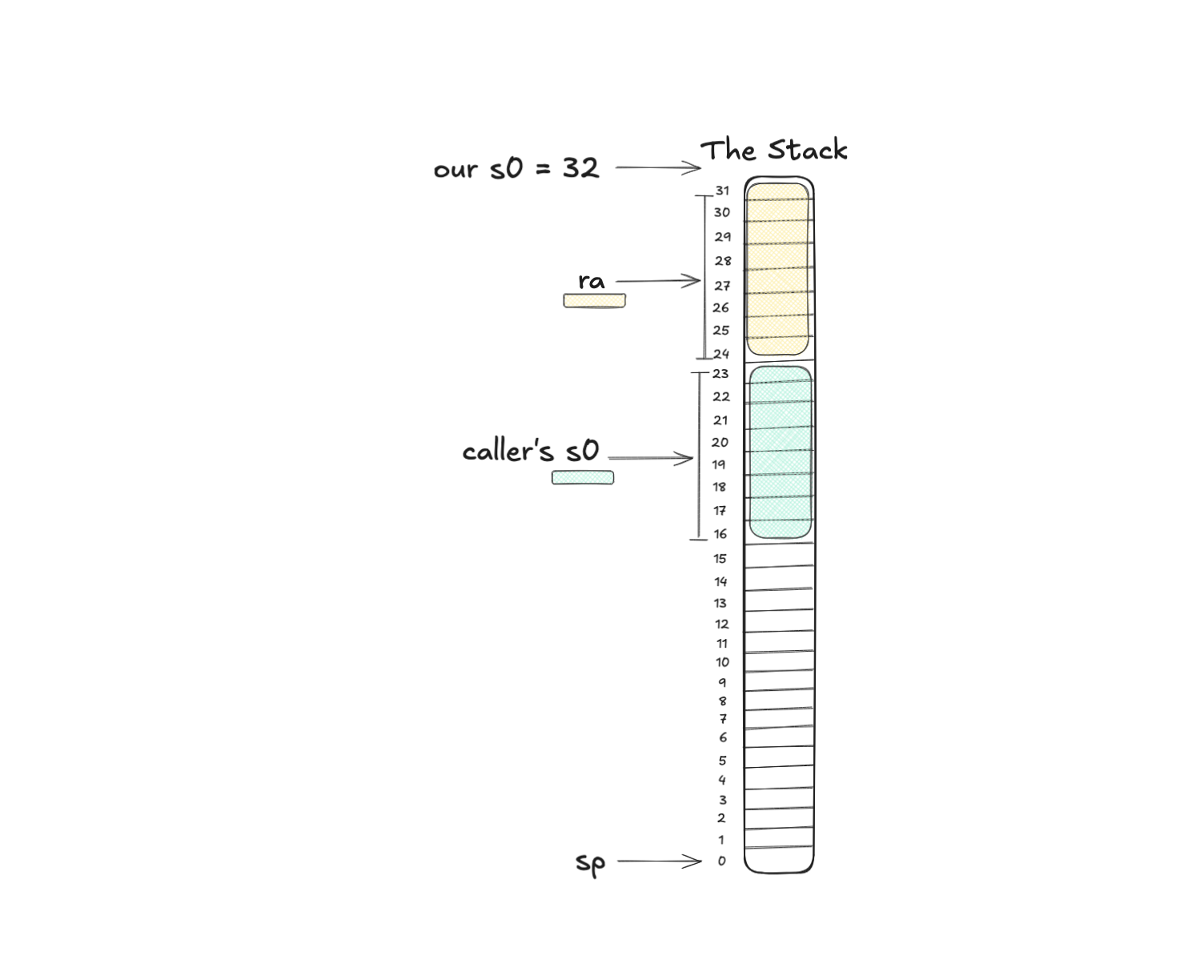

addi s0, sp, 32

Now we can proceed to the next step, and safely create our own frame pointer. Remember, add immediate means:

s0 = sp + 32in our case

s0 = 0 + 32 = 32From here onward, the compiler typically accesses local variables relative to s0 rather than sp. You’ll see that soon!

Okay so hopefully that makes sense. It’s a bit of a weird pattern at first, but this is the most common one you’ll see a lot in assembly. And it’s pretty similar in arm and x86 as well. What we’re doing is setting up the function by making sure we have enough space on the stack, storing all the references to our caller and we’re basically getting ready to execute the function itself.

This next part will be a lot easier to wrap your head around, I promise.

Moving the function arguments

1040e: 87aa mv a5, a0

10410: 872e mv a4, a1a0 and a1 hold the first two integer arguments, int a and int b. Here the compiler copies them into temporary registers (a5 and a4).

In optimized builds this usually disappears, because the moves are actually unnecessary as we’ll see later.

Saving locals and performing the addition

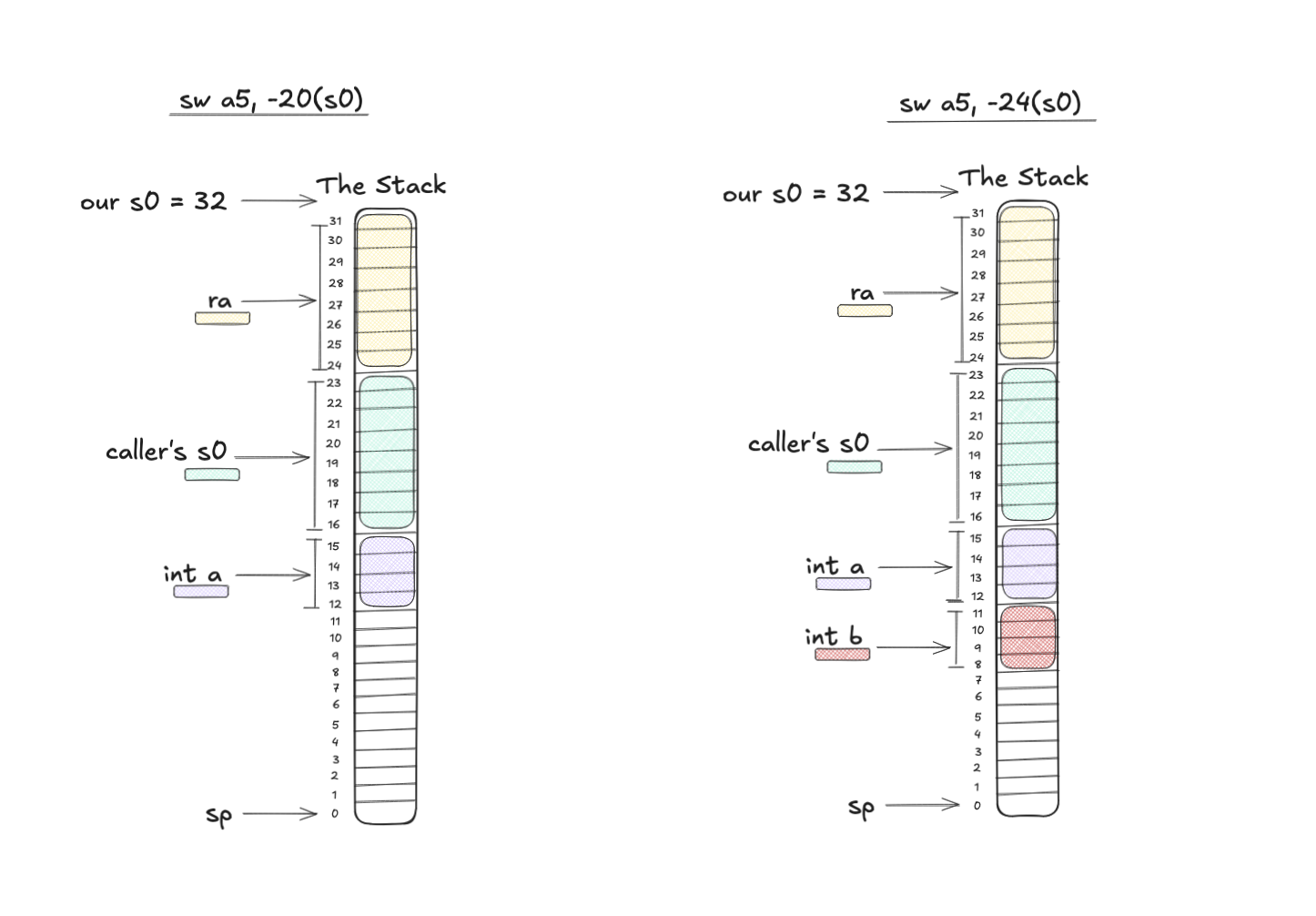

10412: fef42623 sw a5, -20(s0)

10416: 87ba mv a5, a4

10418: fef42423 sw a5, -24(s0)

1041c: fec42783 lw a5, -20(s0)

10420: 873e mv a4, a5

10422: fe842783 lw a5, -24(s0)

10426: 9fb9 addw a5, a5, a4Piece by piece what’s happening is:

- Store whatever is in

a5(which is the function argumentint a) to s0 - 20.swmeans “store word”. Remember s0 was 32. So 32-20=12. And if you recall “double-word” was 8 bytes, logically a word is then 4 bytes. - Move the value in

a4(which isint b) intoa5. - Store the value in

a5, a.k.a ourint b, to s0 - 24, which is 32-24=8.

lwmeans “load word”. So now we’re taking the value at s0-20, back from the stack into a5. Remember this was ourint a.- And now move that value from

a5intoa4. So nowint ais ina4. Confused? Don’t worry. - Load from s0-24 into

a5. This is where we storedint b. addwmeans “add word”. So it adds the 32-bit values in a4 and a5. Finally 🎉

Phew 😅 now that’s a lot of moving data for just adding two numbers. If you think this is silly and inefficient, you’re right! We’ll later look at the optimized assembly for this function, so stay tuned!

Sign-extend and prepare the return value

10428: 2781 sext.w a5, a5

1042a: 853e mv a0, a5This is not super important, but sext.w sign-extends the lower 32 bits to a full 64-bit value, because addw produces a 32-bit result (with RV64 semantics).

And the return value must be in a0, so we move it there.

Restoring the caller’s state

Remember the ceremony we did in the beginning with setting stack and frame pointers? Now it’s time to unwind those.

1042c: 60e2 ld ra, 24(sp)

1042e: 6442 ld s0, 16(sp)

10430: 6105 addi sp, sp, 32

10432: 8082 retSo first we take the return address of the caller, which is at the top of the stack at sp+24.

And we put that into the ra register, this is where we need to go back, it’s the address of our caller.

Then we restore the frame pointer to the caller’s. This is so that when we go back into the function that called us,

it can continue to reference its local variables from the correct reference point. Similarly to how we moved int a and int b always relative to s0.

And then we give back the stack we allocated in the beginning, now the stack pointer is at 0 + 32 = 32, which is what it was when we started this function.

Finally, return!

The optimized version (-O3)

I promised you that I’d show the optimized version as well, here’s the entire function when compiled with -O3.

000000000001040a <magic>:

1040a: 9d2d addw a0, a0, a1

1040c: 8082 retThat’s it! No frame pointer, no stack usage, nothing extra. The addition happens directly in the return register.

And the compiler goes even further when we look at the main function:

000000000001030e <main>:

1030e: 00050537 lui a0,0x50

10312: 1141 addi sp,sp,-16

10314: 95850513 addi a0,a0,-1704 # 4f958 <__rseq_flags+0x4>

10318: 45a1 li a1,8

1031a: e406 sd ra,8(sp)

1031c: 143000ef jal 10c5e <_IO_printf>

10320: 60a2 ld ra,8(sp)

10322: 4501 li a0,0

10324: 0141 addi sp,sp,16

10326: 8082 retNotice anything missing? There is no call to magic at all.

The compiler realized that magic(3,5) is always 8 and simply folded the constant, which is the line with li a1, 8, into the call to printf.

This sort of optimization is extremely common in modern compilers.

Wrap-up

Hopefully this tutorial helped you get a better grip on reading assembly, especially how function prologues and epilogues work, how registers are used, and why unoptimized code looks so strangely verbose.

Happy hacking!